Dr. Weil, on your site’s weekly bulletin, you have a headline of “How To Gain Bad Belly Fat,” and report that “a new study suggests that skipping meals can add to belly fat – the kind that can set you up for diabetes and heart disease – at least in mice.” You go on to say “The belly fat the one-meal-a-day animals put on was determined to weigh more than the belly fat of the mice who could eat at will,” and “The study’s senior author said the new findings support the notion that small meals throughout the day may be helpful for weight loss, but also suggest that skipping meals to save calories sets you up for larger fluctuations in insulin and glucose, which can promote unhealthy belly fat.”

I have to ask: Did you read the article or just the press release from Ohio State University? The study started by restricting the food intake of one group of normal-weight (not overweight or obese!) mice for several days. The restricted group reached an average body weight that was 21% lower than their age-matched peers, which, by the way, continued to put on weight throughout the duration of the very short (18 day) study. For a person with a lean body weight of 150 pounds, a similar restriction would put them down to 118.5 pounds.

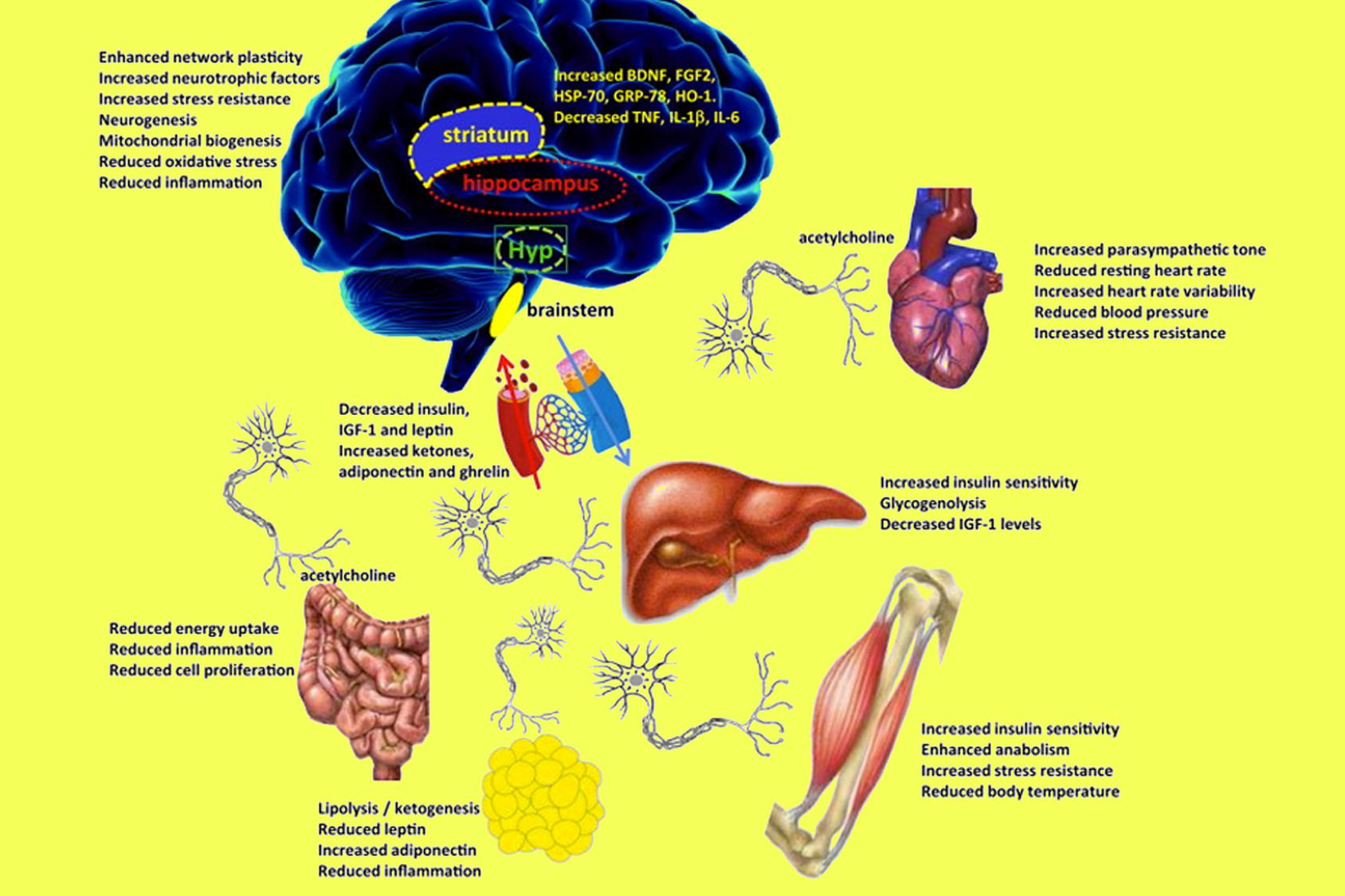

When these underweight mice were then allowed to eat more, but in a limited time, they gorged. The authors indicate that this arrangement of semi-starvation followed by refeeding is known to promote gorge-feeding in mice, but I’m not sure what other behavior would be expected from animals allowed to eat again after famine conditions inducing so much weight loss. The researchers found that the underweight mice put on more belly fat and had less thermogenesis in their brown fat compared to the mice in the control group. This all makes perfect sense; an animal would conserve both fuel and energy when exposed to starvation conditions and an unreliable food supply. The study did not go on long enough for the underweight group to recover to the same weight as their peers in the control group, so we can’t know whether or not they would have redistributed the belly fat once they recovered their normal body weight. The authors also mention that the feeding schedule may have been in conflict with the circadian rhythm of the mice, since the normally nocturnal mice were limited to daytime feeding.

At no time in the study was an overweight mouse put on time-restricted feeding, so the study does not mimic overweight humans eating on a time-restricted schedule. The study may have some relevance to refeeding an anorexic person, or one who has suffered involuntary starvation conditions, or perhaps a person who has lost weight due to cancer or infectious disease. Weight loss on an intermittent fasting (also known as time-restricted feeding) schedule, despite the senior author’s allegation stated above, was not examined in this study. If it had been, the results would likely have been similar to those discussed here.