A French friend (merci, Annabelle!) pointed this out and I’m passing it on. In the USA, we typically ask the question of youngsters at meals, “Are you full?” and if they’re not full, we encourage them to eat more until their stomach has reached its maximum capacity. It’s a bit like stopping at the gas station—we want to be sure the tank is full, not just enough to carry us to the next opportunity to get gasoline. However, unlike when we’re driving a car, with our bodies, we know we’re going to fuel up again within a few hours at the next meal. Unlike fueling a car, it doesn’t make sense to fill the tank to capacity every time we have the opportunity.

Are you still hungry?

That’s why it’s notable that in France, rather than asking “Are you full?,” the traditional question is “Are you still hungry?”

The difference may seem subtle, but it emphasizes the importance that seemingly innocent messages can have in what we’re teaching our kids about food. In the USA, we’re saying “eat until you can’t eat any more.” In France, it’s “eat enough that you’re not hungry.” If you don’t think there’s much of a difference, try this experiment at your next meal.

This is an experiment worth trying!

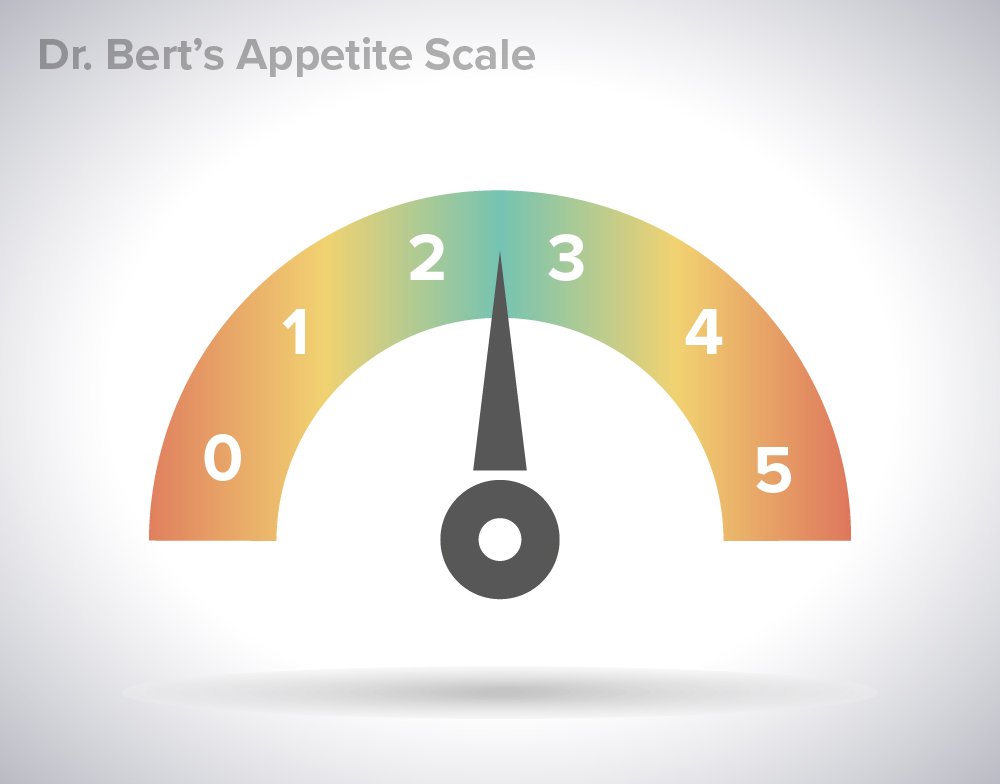

As you begin to eat, you’re presumably hungry. If you’re not hungry, we have to ask another question, “Why are you eating?” but that’s a topic for another blog post. As you eat, try to take note the time, while you’re eating, that your hunger goes away. In my case, it’s completely gone after a few bites. I continue to eat, but a sensation of hunger is no longer driving the process. At that point, it’s simply appetite and habit of eating whatever portion I’ve allocated for myself. There are a few familiar waypoints along the way between that point and my maximum capacity. Applying a 0-5 scale to fullness and satiety looks something like this:

| Level 0 | Still hungry with real sensations of hunger. No feeling of satiety or fullness. |

| Level 1 | No longer feeling hunger, but no perception of stomach fullness. |

| Level 2 | Some sensation of stomach fullness. If called away from the table for some urgent task, one would not feel compelled to return to the meal afterward. |

| Level 3 | Clear sensations of fullness. One typically stops eating at this point if there is no social pressure, habit or delicacy driving further consumption. |

| Level 4 | Stuffed to capacity, perhaps because one has felt obliged to eat more for social reasons like complimenting the cook, cleaning one’s plate or falling to the temptations of a delicious dessert. At this point, one feels full. |

| Level 5 | Stuffed to the point of stretching the stomach beyond its nominal capacity, causing discomfort, sometimes with nausea, often with regret and a need to loosen one’s belt. |

Leveling up adds up quickly!

By asking our children “Are you full?” we’re asking them if they’ve maxed out their capacity—that’s level 4 or 5 satiety. The French version, “Are you still hungry?” asks if they’ve reached level 1 or 2 satiety. The difference in volume between level 2 and level 4 can be substantial. For example, after half a hamburger, you might feel no longer hungry, but it takes the other half—300 calories more—to get to the point of level 3 satiety (feeling full), another 300-calorie portion to get to level 4 and yet another portion to get to level 5. The larger the stomach, the more foodstuff (calories) it takes to get to the next level of satiety. Eating routinely to level 3, 4 or 5 satiety (clearly full, stuffed, uncomfortably stuffed) instead of level 2 (some sensation of fullness) can account for a great many surplus calories.

Kick culture out of the driver’s seat!

In places where food is readily available and one is eating on a fixed schedule, there’s no reason to eat to level 4 or 5 satiety. If additional food is needed, it’s readily available should hunger return. Ideally, we would stop eating at level 2, and if we’re truly hungry later, by all means eat. This hunger-driven approach is unfortunately very difficult in our schedule-driven meal-timing culture. Phony messages embedded in our culture, such as “breakfast is the most important meal of the day,” equating excessive consumption with health (“a healthy appetite”) and traditions like asking “Are you full?” and eating scheduled meals whether one is hungry or not all work together to drive overeating, so it’s culture that we need to fix. We can start changing culture by making different choices for ourselves and by teaching our kids differently.

4 comments

Great article Bert,

I have noticed this distinction a few times whilst using an eating window. Sometimes when my window opens I fully intend to eat a second helping or swing by a take-out joint on the way home but then I decide that, after my first serving, I’m actually not that hungry. So I close the window early or just let it time out.

It is making a world of difference. I’ve tried using an eating window before but, back then, I always ate till I was stuffed-to-the-gills-full and they were much rougher experiences.

So, for me, understanding the difference between being not hungry and being full is a key factor to my having a much easier go of it this time around. You just hit the nail on the head.

Thanks, Rob. I’m glad you’re seeing the difference. When I think about “filling the tank” three times a day, it seems silly now. A full tank (stomach) just to go 3-4 hours? Not any more!

This post shines a HUGE spotlight on one of the root causes of the obesity problem in the US. EVERY word we think or say shapes our life even if we have no idea how powerful language is.

Thanks for your comment, BB! Our culture didn’t develop the overweight/obesity problem in one giant step, and reversing it is going to take little steps like language and what we teach our kids.