When scientists are evaluating an experiment done on mice, they’re usually careful to avoid jumping to the conclusion that what is true for mice in a laboratory cage is true for mice in the wild. The mice in the cage are usually inbred white mice fed a human-made diet. The inbreeding makes the mice fairly uniform, almost like clones, so if whatever is being tested—an anticancer drug, for example—has an effect, it’s likely that it’s the drug under study that made the difference and not genetic variations.

Humans are often studied for various reasons, and when they’re studied, they’re obviously not clones or inbred. They are, however, not really “wild,” either, for several reasons:

(1) They know they’re being observed. Werner Heisenberg is famous for noting that, when it comes to atomic-level events, observation changes the thing being observed. Heisenberg’s principle applies to people, too: they behave differently when they’re being observed. This effect is so profound that in many cases, all you have to do to have people adopt a successful fat loss diet is watch them. They start eating less and are further motivated knowing that their weight will be measured by someone in the near future.

(2) People forget and they sometimes minimize or even lie (not only to others, but also to themselves). Keeping track of every calorie consumed is notoriously difficult, yet a number of studies are based on three-day recall of foods and quantities eaten. Can you remember everything you ate three days ago? Are you going to report the portion accurately after eating half of a pie? Or will it be recorded as “pie, fruit, one serving?”

(3) To get around #2, sometimes studies are done in locked wards, so participants in the study can’t sneak in food or sneak out to get it, which means everything that they eat can be tracked. This tends to be expensive, so studies done like this are usually quite short—two weeks or less—and don’t accurately represent what can happen over several months as people either adapt to a new regimen or fail to do so.

(4) The people available to participate in locked-ward studies may not represent the typical person having trouble with weight gain. Who has time to disappear from the planet for two weeks or more? If you had that kind of time and freedom, would you choose to spend it in a locked hospital ward? Most people with jobs and/or kids can’t do it, and many of those who could wouldn’t choose to.

(5) Recent studies have found that the bacteria in our intestines (microbiota) have a lot to do with how we digest and absorb food. So not only are participants in human studies not inbred, their gut microbiota is diverse too. Unlike the participants’ own DNA, however, the microbiota can change fairly quickly based on the food consumed and the environment (including the external temperature, even though the bacteria are inside the gut where it’s always warm).

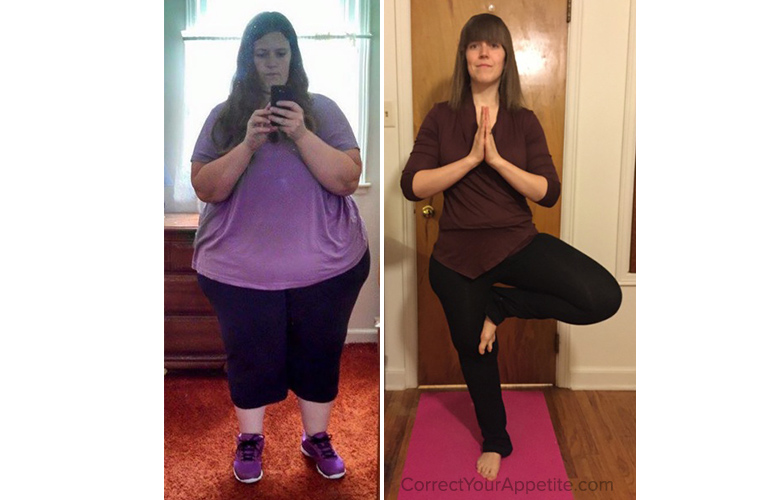

In summary, trying to make sense out of human studies is a difficult enterprise at best. What can we do? Instead of relying on what happens to others, we can see what works for one person in their natural environment. The only observer in this case is the individual. This is called the study of one.

The study of one is a good start, but how do you know what different things to try? The folks at MyFitnessPal (MFP) took a look at what was working for their 160 million users, and reported on the 4.2 million users who had either attained a goal weight or were closing in on it. What were they doing differently from other MFP users who weren’t making headway? They were eating:

- More fiber

- More cauliflower

- More yogurt

- More raw fruits

- More almonds

- More olive oil

- More coconut oil

- More cereal (type not defined; it could be high-fiber or Froot Loops)

- Fewer potatoes

- Fewer eggs

- Less pasta

- Less meat

I was surprised that fish didn’t make the list of beneficial contents, and eggs were on the downside. It’s notable that fiber is the most outstanding component of them all, and the one most likely to influence the microbiota (the bacteria can digest the fiber and derive energy from it to grow; we can absorb some of what remains, but we can’t digest it all without them.) Yogurt, as a source of beneficial bacteria, is also likely to influence the microbiota.

This is not science at its most rigorous, but it is data. It’s data that may influence what you tweak in your study of one. If you’re trying to lose fat, it may go better for you if you eat more fiber, more cauliflower and more yogurt while reducing your consumption of pasta, potatoes and eggs.

The good news is that the people it apparently worked for are real humans dealing with real world environments, just like you. There’s undoubtedly some bias introduced by self-selection:

- People who choose to use MFP are more attuned to their health and diet than those who don’t.

- MFP users are likely to be economically comfortable or better off as indicated by their possession of a smartphone.

Will it work for you? Nobody knows. Just because it worked for some MFP users doesn’t mean it will work for anyone else. That’s what the study of one is all about. If it works for you, that’s great, and that’s all that matters. If you give it a six-week trial and see no difference, then it’s time to move on to something else.

As for me, I’m planning a break-fast of cauliflower with olive oil and almonds, followed by some yogurt with fresh fruit. Bon appétit!

1 comment

Interesting. Good information can come from any source.